Last Updated:

Fixing accent bias requires rethinking how AI listens. Indian English needs to be treated not as an anomaly but as a major dialect.

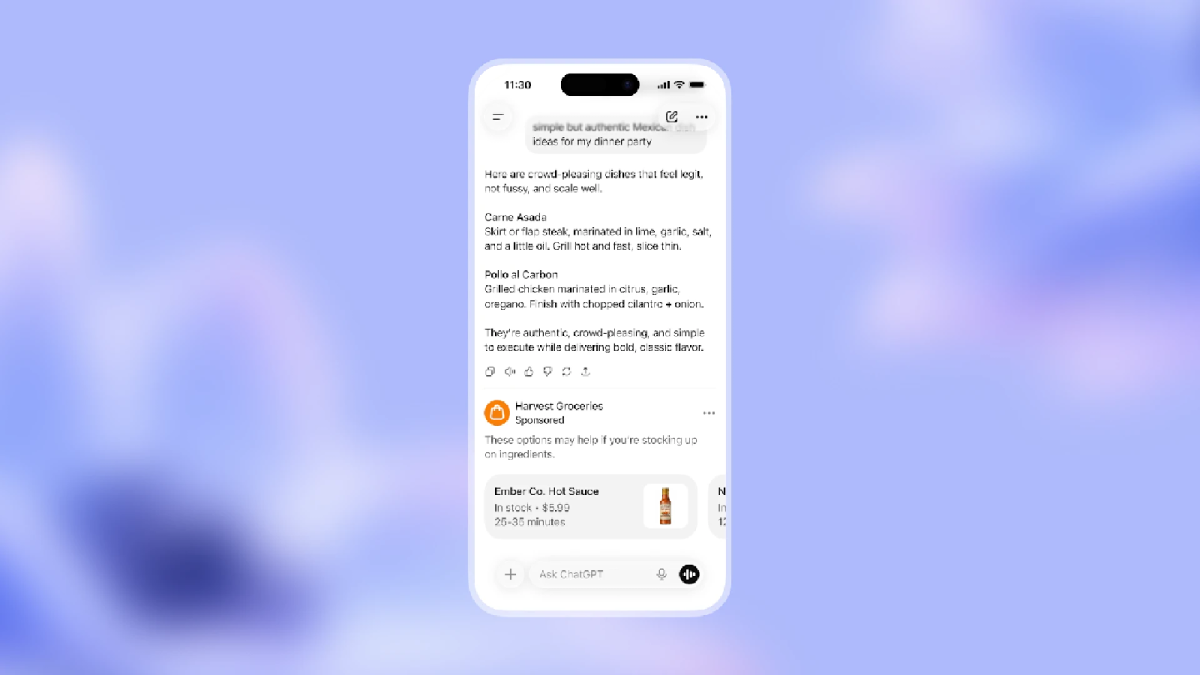

In India, where literacy gaps remain wide, voice input can bridge digital access. Millions of first-time users find speaking easier than typing. (Image: Representative)

It is a familiar frustration. You ask Siri to “set an alarm for half past six,” and instead of confirming, she replies, “Sorry, I didn’t catch that.” Or you tell your car assistant to “play Kishore Kumar,” only to be greeted by random EDM. The problem is not your pronunciation or speed, it is that artificial intelligence still struggles to understand the rhythm and sound of Indian English.

Behind the sleek voice interfaces and digital assistants that promise frictionless convenience lies an uncomfortable truth: most of them were trained to understand Western accents first. For hundreds of millions of users in India, that means digital interactions are often exercises in translation rather than conversation.

The accent bias baked into data

Voice recognition systems learn by listening. But what they listen to, shapes what they understand. When developers build speech-to-text or voice command models, they feed them massive amounts of recorded audio paired with accurate transcripts. If that dataset contains mostly American, British, or Australian English, the system becomes biased toward those accents.

A 2023 Stanford study examining five major voice assistants found that they made two to three times more transcription errors for speakers from South Asia than for native US speakers. Similarly, a Carnegie Mellon analysis showed that Google Speech-to-Text had an error rate of 4 percent for American accents, but 23 percent for Indian speakers using the same sentences.

It is not intentional prejudice, it is statistical imbalance. Most open-source voice datasets still contain less than 3 percent audio from the Indian subcontinent, even though India accounts for more than 15 percent of global English speakers.

When English stops being global

Indian English is not a single accent; it is an orchestra of regional sounds shaped by mother tongues. A Punjabi speaker stresses consonants differently from a Tamil speaker; a Mumbaikar merges syllables that a Delhiite might stretch. Even within cities, code-switching between English and regional words adds complexity.

For example, “switch on the fan yaar” or “call Amma” blends multiple languages naturally. But most AI systems treat them as errors or separate commands. The result: devices that constantly interrupt, misinterpret, or go silent – an experience that feels dismissive to the user.

Why it matters beyond convenience

When technology repeatedly fails to understand a group of people, it subtly signals who the system was built for. Voice AI is no longer a luxury; it is increasingly used in cars, appliances, education apps, and customer service. Inaccessible voice interfaces risk excluding entire populations from these systems.

In India, where literacy gaps remain wide, voice input can bridge digital access. Millions of first-time users find speaking easier than typing. But if assistants cannot process local accents or mixed language commands, the promise of digital inclusion collapses at the first “Sorry, I didn’t get that.”

In sectors like healthcare or banking, such gaps can even become serious. Imagine a voice-based helpline for health queries that mishears “sugar” as “shaker,” or a payment app that misunderstands “send hundred rupees.” For many rural users, these are not small inconveniences, they are barriers to trust.

The economics of misunderstanding

The Indian voice AI market is projected to touch 10 billion dollars by 2030, driven by regional-language interfaces. Yet most global companies continue to rely on Western-centric training data.

Collecting high-quality Indian English and multilingual audio is costly. Each hour of annotated speech data can cost between 20 and 50 dollars to produce.

Start-ups are trying to fill that gap. Bengaluru-based Reverie, Hyderabad’s Skit.ai, and Delhi’s Gnani.ai are developing datasets that reflect local speech patterns, including mixed language queries.

Some have partnered with government projects like Bhashini under the National Language Translation Mission, which aims to build open datasets for 22 Indian languages. But progress is uneven, and many global AI systems still rely on older, accent-limited datasets.

How bias gets amplified

Even when companies attempt to include Indian voices, the models trained on global data can dilute that diversity. Suppose an AI system learns from 100,000 hours of speech, of which only 500 are Indian.

The model still optimizes around the dominant accents because they form the statistical majority. This means that unless the training data is balanced or reweighted, the AI continues to prefer the accent it hears most often.

Another challenge lies in pronunciation feedback tools, the kind used by language learning apps. Research from the University of Cambridge found that such systems often rate Indian English as “incorrect” even when it is comprehensible and grammatically accurate, simply because the pronunciation deviates from Western norms. This reinforces an old colonial hierarchy: one kind of English is seen as standard, and others as flawed.

Building voices that belong here

Fixing accent bias requires rethinking how AI listens. Indian English needs to be treated not as an anomaly but as a major dialect. That means three things: better datasets, smarter modeling, and ethical inclusion.

First, speech corpora must include regional and socio-economic diversity, not just educated urban voices but also speakers from small towns, villages, and multiple age groups. The way a 60-year-old from Coimbatore says “temperature” differs from how a 22-year-old engineer in Pune says it.

Second, models should be tuned for code-mixing, the natural blend of English with Hindi, Tamil, Bengali, or Kannada. This is not a bug in communication; it is the reality of Indian speech.

Third, companies need transparent audits of voice AI accuracy across accents, just as they now report fairness metrics in facial recognition or recruitment algorithms. Inclusivity in AI must mean everyone can speak and be understood, not only those with polished vowels.

Small changes, big empathy

Some global firms have started taking steps. Google Assistant added “Indian English” as a separate voice model in 2019, and Amazon introduced localized versions of Alexa with regional speech cues. Yet most of these systems still perform better in cities than in rural areas. The gap between a Delhi English speaker and a Nagpur or Guwahati speaker remains wide.

Human-computer interaction experts argue that accent diversity should be celebrated, not corrected. Technology should adapt to people, not the other way around. Voice AI that learns from India’s complexity could even set global benchmarks – after all, if a model can understand ten accents from India, it can understand the world.

The cultural layer

Accent is identity. It carries where you come from, what languages shaped you, and how you learned to express thought. When an AI assistant fails to understand that voice, it fails to see that identity.

Over time, users may unconsciously modify their speech to sound more “machine-friendly,” mirroring the old colonial reflex of softening one’s accent for acceptance.

That quiet erasure of individuality is what makes the issue more than a technical glitch. It is cultural invisibility — a loss of voice in a literal sense.

The way forward

India has the scale and linguistic richness to lead the world in accent-aware AI. A combination of government-supported open datasets, ethical private innovation, and multilingual research could redefine how machines listen. The larger question is whether companies see inclusivity as a compliance checkbox or as a design principle.

Technology that listens differently could build bridges where language divides. It could give millions their digital confidence back — to speak in their own way, in their own voice, and still be understood.

One day, when Siri replies perfectly to “Siri, play old Kishore Kumar songs,” it will mean more than progress in speech recognition. It will mean the machine has finally learned to hear us – not just our words, but the worlds within them.

October 13, 2025, 13:46 IST

Stay Ahead, Read Faster

Scan the QR code to download the News18 app and enjoy a seamless news experience anytime, anywhere.